I will have a whole book to convince you of the importance of competition. Let me now have some pages on how I got here.

The only reason I am in this business is Berkshire Hathaway’s annual letters. I was born in 1988 and raised in São Carlos, Brazil, a city of 300 thousand people where investments or financial markets are not mainstream topics. My earliest and fondest memories of any business come from following my father to his family’s local farm. My grandfather had a pole manufacturing business, in which my father also worked but was not very interested. The farm was fun, though. Raising cattle, breeding American Quarter horses, buying new tractors, etc. I just loved it. It felt like something I could do too. And that was true. Anyone with money can “play” farming. It is often the favorite hobby of the wealthy, with the funniest parts of it, such as breeding horses or raising cattle, being the worst ones economically. The boring thing, uninteresting for a child and hard to crackle for an outsider, would have been the better returning activity amid the family businesses: the pole business, which had less than a handful of competitors in our region.

At that time, in my early childhood, power companies, our clients, were still government controlled in Brazil. Let’s just say that their executives were not unfamiliar with their counterparts at main suppliers, who were also not unfamiliar with each other. Before moving on, I want to highlight how despicable, wrong and unforgivable this kind of behavior is, even if it does not cross the line into illegality. I was a child during those years and would just start to suspect these things, the magnitude and depth of which I never came to fully know, much later when life taught me how badly some people can act because of money. That changed though, with the magic of capitalism, i.e., privatization, which came alongside a whole package of reforms in the country, including the introduction of the Real currency in 1994, that significantly modernized our economy.

As we shall see later, pole manufacturing can be good business, as poles are a local product by nature – bulky and of low value. Good, not great though, unable to withstand management practices from pre-privatization times, such as sustaining money losing farms and expensive cars for the whole family. It all came crashing down, leading to bankruptcy when I was a teenager. The initial reaction in our family was denial. And it was not different for me. Bankruptcies in Brazil can be quite protracted and extend for years or even decades before the final nail is put in the coffin. I had grown more interested in business but continued narrowly focused on my path to be a farmer, looking forward to developing and running farms farther into Brazil’s countryside. That was not to be, though. Reality struck. As time went on and the pole business kept sliding I realized that there was no more money available to sustain the future I had imagined. Childhood was over.

I am a naturally optimistic person, and when I think about how this bankruptcy experience during my formative years shaped me, I wonder whether I would have been so quickly and deeply attracted to Buffett’s teachings otherwise. Maybe I would have become a venture capitalist rather than an investor focused on stable oligopolies. Granted, other personal characteristics of mine would have pushed me to the latter, such as my introverted nature and natural aversion to risk since childhood. Knowing yourself is extremely important to define how you will invest, so that your strategy fits your nature, and you can work stably through the inevitable ups and downs.

Having enrolled and begun Agronomics college, I was confused, struggling to chart a new life plan. My degree enabled optional classes in Finance and Administration though, and even if they were neither deep nor great, I somehow found myself reading about the stock market and ended up with a Berkshire Hathaway annual letter in my hands. The clarity with which Buffett explains businesses took me out of the muddle. For the first time in my life, I could make sense of the business world, understand why some firms flourish while others flounder. I read all his letters in a short period of time and began to use that knowledge to help my father restart his life, which was my priority at the moment given that our household was in disarray. I already knew, nonetheless, that I wanted to follow Buffett’s steps and become an investor, but I was clueless about how to do it. The only thing I could see was that if I kept going deeper and deeper into studying his career and past investments, I was headed in the right direction (and enjoy myself).

Seeing the pole business going from bad to worse, my father had begun to build homes, exploiting a new market created by the central government’s then recently launched “My House My Life” program, which provided subsidies and cheap financing for low-income families. Seeing the margins he was making, I jumped into the boat and devised ways to accelerate the business with as little capital as possible – I had just learned from Buffett the importance of high returns on invested capital and keeping the denominator of that equation as low as possible. We succeeded and made good money. I began to organize our financials every three months and write quarterly reports for my parents. Buffett has his global willing audience; I had my tiny forced one.

Soon my reports went from enthusiastic to dire as competition was closing the door on margins. Many people began to build affordable homes, bidding up labor, materials, and, especially, land prices. Land availability was constrained in our city. In the early days of the program, we could sell a very nice home for just a small premium to the amount financed by the government. Soon we found ourselves struggling to find the rare buyers who could pay a much larger premium (3-4x the initial ones), or having to finance the premiums ourselves, taking on more risk just to keep our margins and later to make any reasonable returns at all as cycle times extended. Fortunately, we saw this coming (thank you, Warren, again) and pivoted the firm to be a sustainable construction services provider with low capital employed from which my parents made a good living for many years afterwards. I had felt my first pains from competition.

I learned that fast and furious demand booms create amazing opportunities for well positioned, lucky or foresighted, entrepreneurs to make outsized profits. However, I also learned that unless you have a huge moat protecting yourself, others will hurriedly come to serve that market and end your party, often in disaster. I always remind myself of that when I see profits spike out of normal ranges due to exogenous factors.

Another lesson was that subsidies cannot structurally alter the nature of a market. They just create distortions, often begetting the need for more interventions until a correction of sorts occurs. In this example, given that home buyers were forced to either pay significant premiums out of their pockets above the subsidized amounts or buy very low-quality apartments for inflated prices, it is fair to say that the well-intentioned subsidies ended up being a wealth transfer from the government to well-off landowners throughout the country, i.e. most of the economic value was ultimately sucked and retained by the structurally bottlenecked part of the value chain. From my experience and readings since then, I can generalize that subsidies, as well as other forms of government intervention, are the opposite of competition in a capitalist system. They are usually nothing but wealth transfers from the whole population to subgroups of businessmen.

Let me inject something else here so that you don’t get bored with my personal history. Back to exogenous factors driving profit spikes, Covid was a major one for many companies.

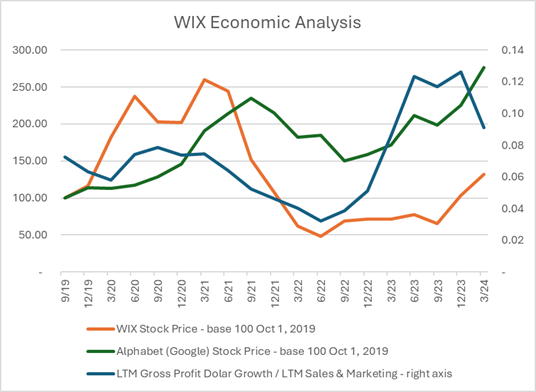

With consumers at home, small businesses rushed to create or improve their online presence. Companies that provide easy-to-use software for website development, like WIX and GoDaddy, saw an explosion in demand. Revenue growth rates skyrocketed. But could these firms retain any extra economic value?

Management teams throughout the industry, as well as venture capitalists funding entrants, got excited with the mirage of a new era of sustained super growth and boosted investments in online ads to acquire more new customers. Given the natural high mortality in the SMB customer base and little product differentiation, the website building industry has always been very competitive, especially in spending for customer acquisition. I like to measure and follow the intensity of such competition by looking at growth in gross profit dollars divided by sales and marketing expenses. During Covid this ratio deteriorated significantly. We can say that WIX and peers became a true conduit of shareholders’ and venture capital dollars into the pockets of Google and Facebook, the true oligopoly/chokepoints of this value chain.

Only the shock from downward spiraling stock prices and arguments from sensible activist shareholders could wake management teams up to reality during the second half of 2022. With venture capital funding in a drought and the largest players all taking similar measures under the same influences, cutting expenses, and accepting the new reality, these businesses have stabilized as I write (mid-2024), but they have retained no economic value from the Covid-driven spike in demand. Google and Facebook have.

Back to me. Concurrently with the changes in our homebuilding firm, I also had to shut down a fledgling supply-chain financing business that we tried to create with a partner, because much larger competitors with cheaper financing and scale advantages on fixed costs were driving us into riskier clients that would sooner or later cause us huge problems in defaults. Yet another lesson on competition.

When I was 23, having helped establish the service-oriented homebuilding company for my parents to run, I decided to shoot emails to every investment firm that had anything related to Value Investing in Brazil, with my preferred one being Tarpon, which Zeca Magalhães had founded in 2002 when he was just 24 years old. By 2011, when I reached out, Zeca and team had grown the business tremendously after momentous success on some contrarian, bold and original investments.

I will not bother you with details, but both I and Tarpon’s HR department made mistakes, and I ended up there on the operations team. I just loved the environment and culture of openness. Anyone could join meetings to discuss investment cases, which I did a lot during the very short period I was there in 2011, not only because I loved it, but also because I just did not know how to do the job I was supposed to do and could not bother my colleagues more than I was already doing.

During one of those meetings, with the presence of all partners and the legal team a discussion about necessary precautions when joining boards of directors of our invested companies came up and got heated, with Shayer, the lawyer/partner, trying to get people’s attention for the significant risks involved, especially in Brazil where many companies have controlling shareholders who often act regardless of what independent board members say. At some point Zeca, who was seated at the edge of the window as he had arrived late, got up, and asked Shayer to move slightly to the side. No one understood it, until the slide projector reflected TARPON on his forehead. Having thus masterfully broken the ice (I would later come to appreciate that despite his amazing brains, Zeca’s best strength is his emotional intelligence), Zeca proposed a simple, brilliant solution: let’s just join boards of superb businesses, in which making and growing profits is so easy that managers and owners will not have any reasons to get anywhere near the proverbial line. This may seem like a lose paragraph here, but we will pull this thread before finishing the book.

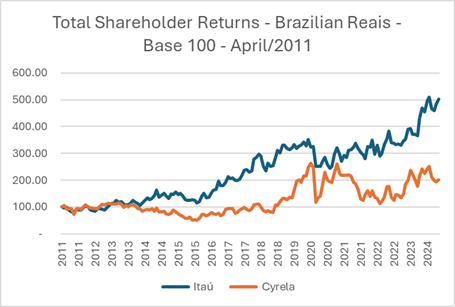

During those days I wrote a two pager, drawing on my experience with homebuilding and Buffett’s lessons on banking and competition, explaining why in my little personal portfolio I was investing in Itaú, Brazil’s largest private bank instead of Cyrela, the country’s biggest homebuilder, despite the latter being apparently cheaper and having some hidden assets.

At that time fintechs were barely existent and competition for core retail accounts was limited amid five mega banks in Brazil. Itaú was the largest and most profitable, with a sticky customer base that was wealthier than its peers’. I reckoned that fees and interest charges are a reoccurring, usually small, often hard to compare, and frequently “imperceptible” expense for clients. Customer churn was extremely low. In that favorable competitive environment, Itaú had a good track record of high returns on equity, despite its conservative leverage.

On the other hand, a new home is the most relevant life purchase for most people. It is an expensive and sporadic item whose buyers are as rational as humans can be in terms of price/value shopping. Moreover, homebuilders start their business almost from scratch with each new project. Doors are wide open to competition every time a new piece of land is available, while banks at that time were very well protected by the trustworthiness of their brands in a country where not much more than a decade before many banks had gone bankrupt.

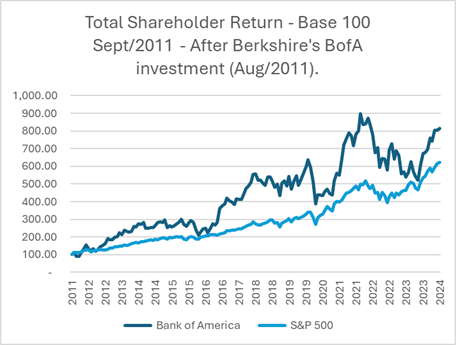

Moreover, a simple study of history would have shown the chaotic nature of homebuilding, with many players coming and going and no clear patterns, while the banking sector had been consolidating for decades with decreasing entropy as leaders benefited from scale advantages to automate operations and lower costs to serve customers. It was not without reason that Berkshire Hathaway had been enjoying a similar trend in the U.S. banking sector for decades, mainly through Buffett’s longstanding investment in Wells-Fargo, which he put together in 1990. Wells had been leading the consolidation process in retail banking and driving excellent shareholder returns. In 2011, Berkshire’s largest sector concentration in its public stock holdings was in financials. Wells-Fargo would later have significant operational and regulatory issues and lose Buffett’s confidence and investment, but even after seven years of substandard performance before he exited the stock in 2022, Buffett’s overall results with the bank were satisfactory. Returns would have been good for someone who had invested in and held Itaú since 2011 too.

It was very simple stuff, but that paper brought me good fortune after I met Leonardo Fração at a Value Investing conference. He was showing people a photograph of himself with Buffett. I had to at least befriend this guy! We exchanged some emails, and I sent him the paper. Leonardo and his partner, Rafael Sá, had recently started an investment firm, completely inspired by Berkshire Hathaway, named Value at the time and soon renamed Nebraska Capital. They invited me to join, and I moved to Porto Alegre, in the very South of Brazil, distant from home.

I was extremely lucky and am forever grateful to them for the opportunity, as I began my investing career with real responsibilities earlier than most of my peers. I was not alone; Rafael was the senior voice on investments, but he was also new to the field and remarkably open to my ideas – he is also among the five wisest people I know. I have nothing but great memories of learning from and with Rafael. We had both studied Buffett and old investment stories at length. But it is only by getting into the field and playing that one really learns.

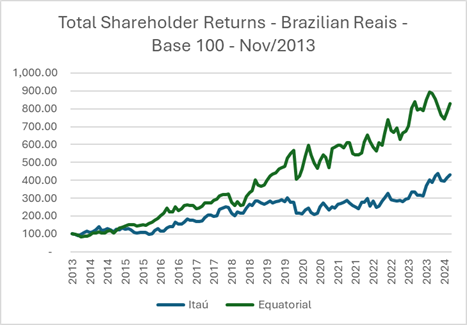

Our best investment by far was Equatorial Energia, which at the time, in 2013, owned and masterfully operated two power distribution monopolies in the North and Northeast of Brazil. These assets are regulated through a benchmarking system by a federal agency. Therefore, you just need to be good enough compared to many other companies who are badly run by either local governments or lazy multinationals, to make a good return on capital; and if you were great on operations, with the right incentives to your team, like Equatorial was, returns could be sustainably amazing. The stock was always “expensive”, and it hurt us to buy it while we were seeing retailers, steel makers, and other manufacturers trading at low multiples. We did it anyway, foreseeing a bright future for Equatorial as the natural consolidator of these regulated assets in Brazil. We could not have imagined how bright though. Today the company owns seven power distribution companies, besides a couple of water utilities, as well as some transmission and generation assets. Monopolies are great, even regulated ones can be so.

I brought Itaú’s stock as a comparison to Equatorial on the chart as I do not consider Brazil’s Ibovespa a good benchmark – it is too heavy on commodity companies, as well as government-controlled ones; Itaú has outperformed it.

Side story, Equatorial also gave me one of the greatest embarrassments of my professional life. A few months before we invested in the company and with me having just a superficial understanding of the business and how regulation worked in the power distribution industry, Rafael and I visited with a guy from a fund much bigger (and better) than ours. He was telling us excitedly about their big investment in Equatorial when I, in my whole low-20s wisdom, interrupted him to say how misguided he was: how could you pay such a high multiple for a company whose earnings were bound to be brought down by regulators?

Fortunately, I have always had the tendency to try to understand things down to the most distillable parts and when I got back home I dived into the regulator’s manuals, equations, etc., and I grasped it all. Not only were Equatorial’s high returns on capital sustainable for as far as a large swath of peers were badly managed by local governments or foreign owners, which likely meant decades, but also the company would compound earnings aggressively by investing substantial sums to grow households serviced and quality levels at its two markets and potentially through sector consolidation as it was just one of two local companies with real expertise and balance sheet strength to take on struggling peers. When it all dawned on me, I felt so embarrassed that I hoped my path would never cross that guy’s again. And I learned to keep my knee-jerk reactions, which are usually stupid, to myself.

I wish we had just deployed all our capital in Equatorial and gone to the beach for a decade. But we had to learn through pain as well. Enthusiastically perusing our stock market for opportunities, we found them, often at the wrong places though, like trucking companies and steel makers, as I worked hard to convince myself and my partners of the “quality” of these companies. Obviously, it did not take long for us to learn about how easy it is to buy a truck and compete, or how fickle profits in steel can be once Chinese players start dumping their excess output all over the world.

As we learned our lessons and narrowed our focus on genuinely great businesses, our universe of possibilities in Brazil shrank. However, since my first days at Nebraska I was trying to manage a small portfolio of stocks in the U.S. as well, mostly during my idle time. That was easy initially, as it being still early in the economic recovery after the Great Financial Crisis, I could just follow my mentor Buffett into names that seemed exceptionally obvious to me, like Bank of America trading at a big discount to book value after it had cleaned-up its balance sheet. Great times.

As these investments worked, and I learned more about the American society, culture, and businesspeople, I got hooked. Over the years I dedicated more and more of my time to the U.S., to a point where, in 2019, I was eager to focus only on it. That was when, having always kept some contact with Zeca, I found him reformulating Tarpon in a way that appealed to me, and we decided to join forces, or better, he graced me with Tarpon’s support, to start the fund I currently manage.

Notwithstanding all the lessons on competition during my life until then, I had to burn myself again during 2020 and 2021, when Covid disturbed the economy, and I took some digital companies for granted and bought the proverbial pig in a poke. Fortunately, the lessons came quickly and accompanied by a generalized downturn in the market in 2022 that enabled us to go back to basics (and Buffett’s lessons) and reshape our fund according to our current golden rule of just investing in time tested oligopolies. That is all that I think about since early 2022, i.e., how to identify the best, most durable oligopolies and build a nice portfolio of them for my clients. In the following chapters I attempt to clarify all the thoughts and learnings over these last few years of intense work, as well as from my life experiences. I hope you find it useful.

I am extremely grateful to everyone at Tarpon, and Zeca in special, for supporting and helping me grow during these years. Tarpon’s embrace is particularly valuable for me because I have a peculiar way of working and organizing my days.

When I look back to my childhood, I realize I have always loved to study by myself. My passion is to study businesses. Companies are fascinating living organisms through which one can learn so much about people and life. I enjoy pretty much meeting people to talk about business, but I have even more fun going down a rabbit hole on my readings and data gathering, deciphering raw material, such as old annual reports, industry publications and recorded words from executives. I don’t like to read others’ research notes and conclusions. I see myself as a student who uses his learnings to make occasional investments. I would love if the stock market opened just once annually, so that I could spend all the other days studying in absolute peace.

I have learned that the best way to optimize my life for these characteristics of mine is to live distant from temptation and noise. I live in my hometown city, a three-hour drive from São Paulo, Brazil’s financial capital, where Tarpon is located. There are no peers from the financial world here. I despise the greed game prevalent in Wall Street and our version of it, Faria Lima Avenue. I dread the psychological consequences of that game. Water-cooler chat on stocks is damaging for me, on macroeconomics and politics even more so. I am still amazed by how much part of a team Zeca and everyone at Tarpon make me feel despite the physical distance.

As I finish this chapter you may be wondering “Ok, I got the message already: identify the oligopolies at the top of value chains and put your money on them. So why read further?” First, if you like businesses like me, I will have many more great stories throughout the book. But that is not the main reason.

Consider the profitable Airbus/Boeing duopoly. These companies are the typical OEM (Original Equipment Manufacturer), like car or truck makers. They make most of their profits and cash flows when they deliver airplanes to clients. Boeing has some aftermarket revenues, but it pales in comparison to its profits on the initial delivery. Airbus is even less exposed to aftermarket profits. Management incentive, therefore, is to always deliver as many airplanes as possible, which would entail meeting peak demand when airlines’ all over the world are enjoying highs on their businesses and feeling greedy, but, potentially, seeing downturns alongside their clients when the market gets oversupplied, a scenario in which the stronger position when negotiating aircraft prices would go to airlines, as Boeing and Airbus would see themselves fighting for orders to fill their production lines.

Today these companies have long order books that will keep them disciplined for years. But true long-term shareholders should ask themselves: how can we be confident and invest in this duopoly trusting on sustainable and growing profits for decades? Must we just pray that they will always be managed by highly disciplined CEOs who will not meet airlines’ demand during peak periods? That seems too much to ask of human nature.

AerCap is the largest aircraft leasing company in the world (airlines usually have a mix of fully owned and leased aircraft). It acquired GE’s leasing subsidiary in 2021. During its 2024 Investor Day, CEO Aengus Kelly, who has worked in the industry since 1998 and has held his current title since 2011, said he has never seen any sustained period of aircraft oversupply in the market. And the reason why is in the second layer of the industry’s pyramid, the engine makers, which are our preferred businesses in the sector.

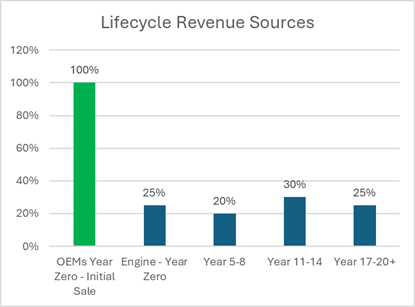

Aengus showed this information above in one of his slides and argued that the industry will not get to structural oversupply because the “engine guys won’t allow it”. His point was predicated on the fact that engine makers make 75% of their revenues from aftermarket services, and, therefore, have all the incentives to preclude the OEMs from flooding the market with excess aircraft that would shorten the useful life of the existing fleet.

Granted, Aengus has some bias to make this argument, but the slide does not even tell the full picture. Engine firms often lose money on new engine deliveries and have perhaps their most profitable revenue event in that last repair shop visit. Hence, their management teams, even if they were shortsighted and just trying to maximize near-term profits for Wall Street, have no incentives to produce as many new engines as possible. To the opposite, they must guarantee that there will be incentives for airlines to spend tens of millions of dollars on that last shop visit to keep old aircraft flying for additional five to ten years, and the only way to do that is to make sure there is no economic alternative in the form of cheap new aircraft available. Moreover, to be wise and long-term superb managers, they should strive for an ever-balanced aircraft market, consistently selling new engines with top-notch technology that will drive growth over the long-term as each new generation comes with higher revenue per shop visit than older versions due to technological advances, without losing revenues from foregone repairs of old engines.

We will go deeper into the aerospace engine industry in the chapters about stage of industry development and industry structure. There is much more nuance, like monopolistic situations within the oligopoly and prior periods of heightened competition, as well as great stories, in this incredible industry.

Coming back to the question of why read further - I brought this dynamic of incentives between layers of the aerospace industry as an appetizer for the kind of nuances in competitive behavior, industry structure, and other aspects we will consider in depth for many sectors throughout the book.

4- Capitalism is Great, and Dreadful

In just 250 years, a short period in human history, the closest experiment humans have had to a pure free market system has created the most prosperous society in the world, by far. Yes, I do love America and all it represents. But I will stop here as this book is not about politics.

Capitalism is a beauty, by far the best economic system for society as it creates wealth by allowing and incentivizing ambition, catalyzing positive sum games, and allocating human and capital resources better than any other system can do. But it is not necessarily beautiful for every individual capitalist. The essence of the system is freedom. In a pure, theoretical capitalist society individuals are free to pursue wellbeing, and the easiest way to do so is to copy what high earners are doing.

Imagine a very primitive capitalist village, where shoe artisans are making a better living than the average worker. Sooner or later, some people will find a way to learn the craft, compete away the shoemakers’ excess earnings and create economic value for shoe buyers, unless the incumbents organize and lobby the local authorities to just allow people to make and sell shoes after a protracted period of low-paid apprenticeship with one of the incumbents, which is exactly what happened in the Middle Ages. Capitalism is, thus, never pure. Even so, it is far purer than socialism or communism, in which a minority of “leaders” manipulates the whole system for their advantage, through dirty and hypocritical psychological maneuvers to deceive the public and stifle ambition, creating a negative sum game that leaves everyone but themselves worse off.

In capitalism, not only do laborers compete for the opportunity to create and monetize value for others, but also capital, accumulated over time, competes for returns. And that competition is dreadful. Through centuries, if the capitalist is not willing to take risks, real rates of return on his savings have been extremely meager, in the low single digits or even negative. Most of us seek a better future though and put our money at play, either to undertake a new business idea ourselves or to, directly or indirectly, help others do so.

Not all humans are optimists, but there are more than enough of us out there to launch an ever-flowing wave of new ventures, not to mention the creatives and inventors who often create industries even if unintentionally. Most of these ventures fail, but some flourish only to attract a ton of copycats. As backers of these enterprises, shareholders are interested in returns on invested capital, which, on average, will always be low given competitive forces and an unending supply of capital and optimistic entrepreneurs. These returns are far from well distributed, though.

A small number of companies will manage to create substantial and durable returns. Due to luck, foresight, superb execution, or a combination thereof, as well as regulatory capture in some cases, these rare exceptions find themselves relatively immune from competition. I will not cover the basic theories about sources of competitive advantages like network effects or scale in this book, assuming the audience is already familiar with them. But the reality is that those are rare and that the few fortunate companies that enjoy them for extended periods end up accumulating so much wealth and compounding capital at such high rates of returns that for the average return on capital in the system to be ok the remaining majority of firms must have meager returns. In many cases competition wreaks further damage and ventures not only fail to generate returns but also cut or erase the value of the initial investment. Notwithstanding this reality, we must remember that there is hardly such a thing as a forever lasting competitive advantage in capitalism and even the winners will sooner or later at least lose some of their powers – one just needs to look at the turnover at the top of the S&P 500 or the Dow-Jones indexes over the decades to see this happening.

Moreover, as society advances technologically, further concentration and scaling of returns with fewer and fewer winners has been the norm. Whereas a century ago the media sector created local oligopolies in newspapers, decades ago, with the advent and spread of television technology, excess returns in media migrated to national oligopolies, like CBS and ABC. These, in the internet age, have been supplanted by a few global winners, like Facebook, YouTube and Netflix, that are sucking all the economic value in the sector. Technological progress underpins these waves. To furnish daily fresh news, even when those came through the telegraph, newspapers relied on local printing presses and physical distribution that precluded the formation of national organizations. Cable, broadcasting, and satellites then enabled distribution of news and entertainment concurrently to much broader geographic areas and audiences. The internet now allows it globally. And the most recent wave comes from AI-based recommendation algorithms that serve tailored content for each one of us at a scalable manner, something that very few companies can do due to the breadth of data, content, and compute power (capital) that is needed to compete. Technology catalyzes power-law returns.

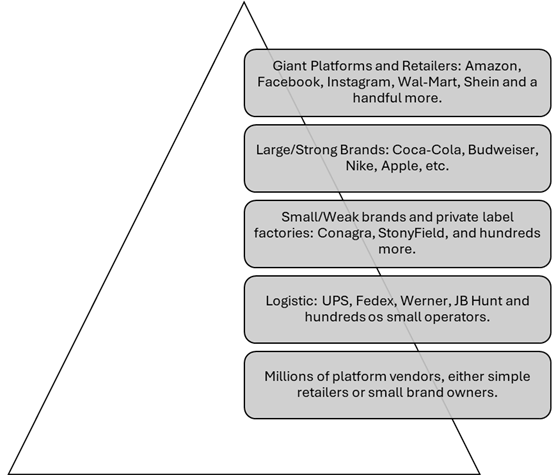

And who pays the price to enable, today and in the past, excess economic profits at media oligopolies? The millions and millions of advertisers bidding for eyeballs on social media feeds or YouTube, trying to sell undifferentiated products and services to fleeting customers. By “pay the price” I mean that these millions of companies will, on average, deliver meager returns to their owners.

Sam Walton was famously innovative. He developed supply chain management systems ahead of peers to lower costs and ensure product availability; he made great use of early satellites in the 80s, boosting his company’s prowess in inventory management and data intelligence. It would have been impossible for a national (and later global) highly efficient retail juggernaut like Walmart to have appeared and dominated over local players were it not for advancements in computer and communication technologies. More recently, Shein, the rapidly growing online apparel retailer, is using machine learning and high-tech logistic systems to coordinate an amazing supply chain that pushes thousands of new SKUs every day and AI-generated ads and land-pages to captivated customers all over the world, smashing even large national retailers that had once used technology and scale to gain market share from mom-and-pops, in yet another example of technology driving further concentration of economic value.

Who pays the price to enable excess economic profits at Walmart, Shein, and other large retailers that scaled to once unprecedented levels? I bet that Walmart suppliers were better off when they dealt with fragmented retailers that lacked data analytics and did not even consider investing in private label brands to capture additional economic value. Shein’s suppliers, factories based in China for the most part, are not likely to make great returns on their investment either. Owners of logistic assets that end up being coordinated by these retail giants that deploy technology to optimize efficiency probably enjoy meager returns as well. And, finally but not least, competitors that saw their businesses be crushed, like department stores.

The ultimate business model in retail is, obviously, Amazon, which I define as a technology driven platform/infrastructure to coordinate the whole value chain, push efficiency as it promotes competition in all layers beneath itself, create tremendous value for consumers, and capture some of that economic value for itself. While Lina Khan (previously an academic who is chair of the FTC as I write it) criticizes Amazon for exploiting suppliers, I would argue that the company is wisely using technology to significantly augment competitive forces that would naturally occur, because of capitalism, in the retail value chain.

Amazon has invested hundreds of billions of dollars to create software and physical assets that enable entrepreneurs from all shapes and sizes, from big brands and those willing to do more of the work themselves to the archetypal solopreneur sourcing products and coordinating everything through Amazon without leaving his home, from anywhere in the world to compete for and create value to consumers in a wide array of countries. It is an amazing feat that would have been impossible with technologies available decades ago. Jeff Bezos’s unbridled and almost crazy optimism was a key component for the company’s success too. He plowed all profits, and some, back into the business, driving technological innovation, expanding the company, and going vertical in ways that most investors and analysts doubted. Bezos ended up creating the most value by far amid his peer group, leaving other e-commerce players in the dust, including early favorites like eBay - we will come back to that later in the book, when studying industry stages.

Amazon creates value for both sides of its platform. For consumers not only through low-prices and speed, but also by an ever-growing and evolving catalog of products that is just possible because small businesses can use the platform to easily reach millions of potential consumers with all sorts of innovative offerings. Automation and outsourcing of functions like customer service, customer acquisition, and logistics to Amazon’s software driven platform enable companies at the supply side of the network to play. Most of them, however, are unlikely to make great returns – after all, Amazon’s platform fosters competitive forces in a super-charged “mini” capitalist ecosystem.

Also, whereas e-commerce package delivery was once the realm of incumbent logistic providers, such as UPS and Fedex, that enjoyed high returns on their assets, like distribution centers and trucks, Amazon has not only invested to own and replicate a lot of these assets itself, but also enabled hundreds of entrepreneurs, large and small, to bring their own vehicles, warehouses, and labor to the logistic system that Amazon coordinates, in yet another way to create value for consumers by unlocking capitalism’s competitive forces.

In the retail pyramid below, I put Facebook and Instagram in the top layer because millions of merchants are heavily reliant on these apps for customer acquisition and hundreds of millions of people have the habit of scrolling through their feeds as a shopping experience.

Retail has never been an easy business – the history of the sector shows that there is hardly any competitive position strong enough to last forever or withstand management oversight. For instance, Walmart’s operating margins at scale and maturity are in the mid-single digits. Amazon’s operating earnings as a percentage of gross merchandise value transacted on its platform, even in its most profitable and developed market of North America, is also in the same ballpark. And both businesses require significant capital investments. Undoubtedly, these companies generate much more value to society than they capture for their owners.

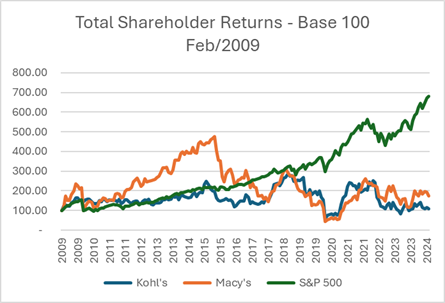

Reality has been hard for prior leaders who rested on their laurels, lost focus, or tried to capture too much value. Sears is a great example of how dreadful capitalism can be for shareholders, who, in the case, could not have imagined where their company would be just a few decades from its pinnacle, marked by the inauguration of the 110-story Sears Tower, then the world’s largest building, in 1974. Kmart, Walmart and others were coming hot for Sears though and it was a downward spiral from there as the company shuffled through different CEOs and strategies but could not arrest the eventual decline.

The ultimate examples of unwavering progress and highly advanced and complicated technologies as the main forces driving market concentration and power-law economics can be found in semiconductors. The industry is filled with oligopolies throughout its value chain, an uncommon circumstance. In some layers they tend to be less durable, in others to have lower returns on capital, but concentration and healthy returns for the winners have been the norm. I will not waste the hottest example (I am writing this during the NVIDIA/AI year in the markets) so early in the book, however. We will dive deep into the sector’s layers in the chapter about durability.

We must remember though that technological progress is far from the only force upholding oligopolistic positions. In many cases it is but a small or negligible contributor. Coke and Pepsi’s, as well as Hilton and Marriott’s, superior and long-lasting returns are largely supported by humans’ craving for consistency and predictability.

Vulcan Materials and Martin Marietta have both delivered superb returns by consolidating the aggregates industry, which is composed of stone and sand quarries that are local oligopolies with low fixed costs and great pricing power due to the bulky nature of their products, as well as “not-in-my-backyard” regulatory constraints on new supply. Even though both management teams talk about technology adoption, I bet their returns would be virtually the same without it.

In other cases, such as in the next couple of examples that you will see on the next post, technology is an important force, but not as singlehandedly relevant as it is in semiconductors. One thing is clear, nonetheless, significant technological progress, when coupled with stable oligopolistic positions, creates huge gains for stakeholders broadly and enables power-law economics for shareholders. These leading companies end up touching so many people and influencing so much business activity that they can capture just a small fraction of the value they generate to their value chains and stakeholders and still grow revenues and profits gangbusters, rather than fight with competitors and stakeholders in a zero-sum game.