1- Preamble: Value Accrues at the Top of the Value Chain

“Think airlines. Here a durable competitive advantage has proven elusive ever since the days of the Wright Brothers. Indeed, if a farsighted capitalist had been present at Kitty Hawk, he would have done his successors a huge favor by shooting Orville down.” – Warren Buffett

Thanks for reading Guilherme’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

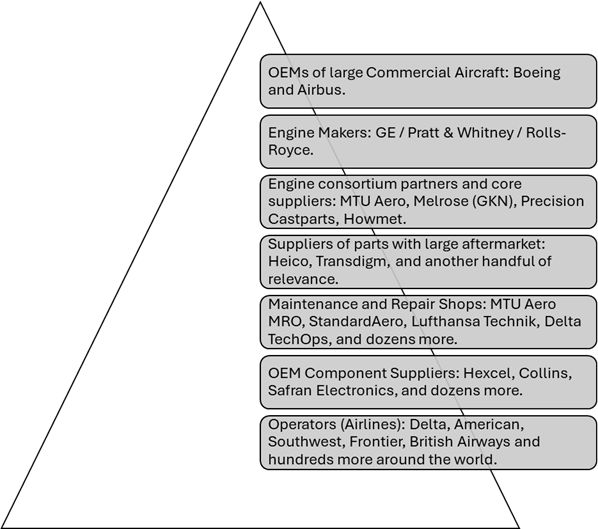

This coming from the master, I can only agree. Airplanes did not bring just airlines into existence, however. A whole value chain has developed around these wonderful machines to enable a larger and larger share of the global population to travel farther, cheaper and safer. Let’s look at it:

We could make the pyramid much more complicated and encompassing. There are overlapping pyramids to fully serve customers if we zoom out to the broader travel industry, like one for distribution, with Google, Booking, Expedia, Global Distribution Systems (GDS), and old-fashioned travel agents, and another one for airport infrastructure and services. For our purposes this illustration is enough though. The fact is that at the bottom the airline industry is terrible for capitalists, with virtually no barriers to entry or expansion (it is easy to finance planes), and horrible competitive incentives given that seats become worthless and that airlines have a hard time differentiating themselves.

For decades, all over the world, we have seen the names of major airlines come and go. Storied ones, like PanAm, TWA, and Brazil’s Varig, have completely disappeared, while others like American Airlines have wiped-out shareholders. Travelers, meanwhile, continue to benefit from either greater comfort or cheaper fares, both with higher safety. Employees have done fine too. In other words, the competitive dynamic in this part of the pyramid do not enable economic value creation for shareholders. (There is a slight chance that this is changing for a couple of players in the U.S., but it is still too early to call it a day – maybe we will revisit it on the next edition of this book ten years from now.)

On the other hand, at least at the three highest levels of the pyramid there is substantial shareholder value creation. People often conflate tech companies for digital ones, like Google or Amazon. But the reality is that Airbus, GE, and peers are high-tech businesses, which have been accruing expertise, patents, and advantages from industry standardization and regulation around their technologies for decades. All of that has not only created almost insurmountable barriers to entry but also led to extreme consolidation. These companies are the chokepoints for the industry’s growth. The buck stops at them. They are the ones ultimately driving affordability, comfort, safety, and economic value for society. Unlike airlines, they can retain a good chunk of this value to their shareholders. Why? Because they are unbreakable oligopolies at the top of the value chain. I will delve into that throughout the book.

I am a fund manager at Tarpon, an independent investment firm based in Brazil. I am responsible for our U.S./Europe Equity funds. Here is our mission statement:

“Our goal is to be a conventions-free capital allocator focused on selected, deeply rational, and long-term oriented equity investments that enable our clients and partners to participate in the constant and dynamic innovation and value creation at the top of value chains in the global economy.”

And its complement: “At the top of value chains is where oligopolies live.”

2- Guide to the Book

My purpose with this book is to organize as much of the learnings I have gathered about competition throughout my life as possible. These learnings encompass many aspects and ways to think about a company’s competitive position and its prospects, from rather tangible ones, such as the physical nature of a product, to intangible considerations, such as the set of incentives driving behavior among clients and management teams. I will make extensive use of examples, some of which will recur in different chapters. In most of the cases we are going to study I will place a huge emphasis on the industry’s value chain and its layers.

Bearing in mind that many aspects surrounding competition overlap each other and that this will be reflected in the book, here is a guide:

Chapter 3: I will tell you about my professional career and life experiences, bringing examples of businesses and stocks that have shaped my investment rationale.

Chapter 4: We zoom out and look at capitalism, its beauty and perils. This is a big one, in which we will see many examples and clues to analyze competitive positions.

Chapter 5: A short one in which we will think about the often-overlooked indirect competition.

Chapter 6: We study the stages of an industry and how they affect the competitive landscape as well as risks and prospective returns for shareholders. Alongside chapter four, this chapter and the next two constitute the core of the book – they are all long, with many examples.

Chapter 7: Many case studies of how industry structure, i.e., how business is conducted in practice, and incentives affect competition and returns on shareholders’ capital.

Chapter 8: We will dive deeply into one industry as we think through the concept of durability of profitable oligopolies.

Chapter 9: A short one about business cycles and how we should be cautious about their effects before drawing conclusions on a company’s competitive situation. We will also look back at cases from earlier chapters to clarify the difference between economic cycles and competitive cycles.

Chapter 10: As a sequence to where we left on the previous chapter, we think through the implications of the competitive cycle for returns.

Chapter 11: Some remarks about B2C versus B2B business models in general, with an interesting case study – and some bias.

Chapter 12: We go deeper into another often-overlooked aspect of competitive dynamics, the go-to-market construct of an industry.

Chapter 13: To the satisfaction of one of my partners at Tarpon, we look at niche markets and strategies to play in them.

Chapter 14: We take a quick look back to some examples from the book to remind ourselves that there are risks at the top.

Chapter 15: With examples, we will see how the best companies, with the most durable moats, are often, if not normally, underpriced in the stock market and try to understand why, while also considering deeper aspects, especially risks, that long-term investors should pay attention to.

Chapter 16: We discuss the ultimate “competitive” threat.

Chapter 17: A brief closing.

3- How my Investing Rationale Got Here

I have erred more than you can imagine. I hope to have learned a lot too, with the most important lesson being to dread competition. It is clear to me now that the main driver of shareholder returns over the long term is the company’s competitive position, as well as its first derivative, whether it is improving or weakening. It is not geography. It is not one industry over another. It is not growth – growth can be great if the company is highly protected from entrants and has high returns on capital, but terrible otherwise. And it is not management.

Superb CEOs can do a lot but will rarely be able to overcome the economic reality of a bad business, unless they just get out of it as Warren Buffett did with textiles. William Thorndike’s great book “The Outsiders” depicts other leaders who created tremendous shareholder value through their decisions and actions, but those were mostly based on wise capital allocation insights like Buffett’s, rather than on operational brilliance.

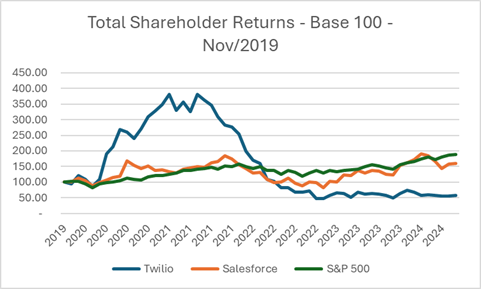

In 2019 I had lunch with one of the wisest and most skeptical investors I know – no, it is not Charlie Munger, but he seems to be on his way to that level. At that time, high-growth SaaS (Software as a Service) companies were all the talk, and, within that industry, people were particularly excited with the API economy. API means Application Programming Interface, and API companies provide software developers with easy-to-use pieces of software to integrate into larger systems they are working on. Stripe is an example of an API company, providing payment solutions. Twilio is another, offering APIs that enable developers to embed communication solutions, like messaging, security verification, and phone calls, into their software systems to make customer service more convenient and automated amid other use-cases. We could not avoid talking about software and Twilio.

Twilio is an impressive company, and its founder can be considered a visionary in software, having brought to life the CPaaS (Communication Platform as a Service) sub-segment of SaaS (Software as a Service). Twilio was running hot in 2019, with high-growth rates and a cult-like following in the software community. Salesforce, which the skeptical investor brought up as a contrast to make his point, meanwhile, was already seen as an old, unexciting SaaS vendor. If you were an academic looking for the company with the highest revenue growth prospects for the next few years between the two, you would do well by following the crowd’s enthusiasm with Twilio.

If you were a capitalist looking for wealth creation, however, you would need to be much more thoughtful and skeptical about your choice. As that investor told me, while Salesforce had all the characteristics of a software product that leads to a great business, Twilio had virtually none. Salesforce core products, customer relationship management, customer service, low-code development platform, and data management, are all highly intricate systems that are deeply integrated and ingrained into their (mostly large) enterprise customers’ operations – to summarize, they are hard to replace. Moreover, replacing them would require re-training large swaths of a corporation’s talent pool, as well as buy-in from millions of small and large IT service providers and resellers globally.

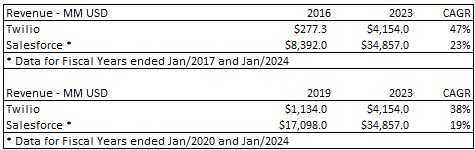

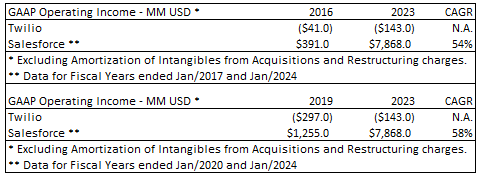

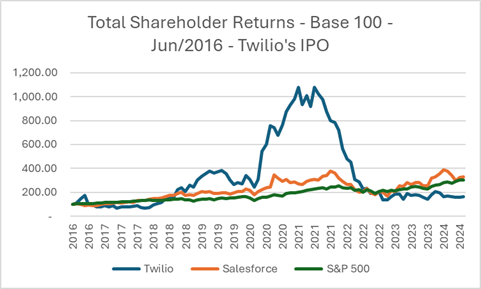

Twilio’s APIs, in contrast, can easily be replaced, requiring just some effort from software engineers – other employees would not even notice it. Moreover, Twilio’s customers are often other software companies like Salesforce itself – these clients’ core competency is to write software as efficiently as possible and they will always be open to cheaper alternatives, even if they need some extra work from their engineers. When the API wave was in its early stages, with companies large and small just starting to adopt these novel solutions and Twilio’s bill was not big enough to raise eyebrows in CFOs’ offices, all was fine – Twilio had “pricing power”. As those bills skyrocketed with usage, however, a wave of competitors saw the chance to bring good enough solutions to the market, at much lower prices. Software developers might still love Twilio, but their CFOs and bosses will eventually call the shot on which provider to use. The table below, as well as Twilio’s so far unsuccessful pursuit to acquire and grow into normal SaaS solutions, clearly depicts the difference between those two business models for shareholders.

The skeptical investor may have sounded out of touch for a while during the market’s craziness in 2020/21. But the stock market ultimately reflects the economic reality of each individual business – from Ben Graham: “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

Since Twilio’s IPO

Since November 2019, when that lunch happened.

Twilio’s founder, Jeff Lawson, having no super voting rights, lost his job as pressure from activist investors mounted and he could not deliver layoffs and cost cuts fast enough to offset the challenging competitive nature of his business. Things got so ugly that revenue growth has slowed to a trickle. Meanwhile, Marc Benioff, who is also a small shareholder with no super voting rights at his company, when confronted with activists demanding better profits, could manage to deliver to their expectations by cutting expenses and relying on Salesforce’s sticky products to continue delivering reasonable sales growth, which, at high gross margins, easily produced mouthwatering incremental operating margins.

Don’t get me wrong though. Other than regulated oligopolies like water utilities, no business is magically born into an amazing dominant and durable competitive position. Marc Benioff has certainly been a brilliant CEO who attracted a superb team of colleagues. Over years and decades, they have made thousands of great decisions, which have far exceeded their mistakes, and executed well on their vision of delivering customer value. From how to build workflows in their core Customer Relationship Software (CRM) to how to develop their sales team, they have outmaneuvered and outperformed many competitors to get to their dominant position.

At some point in the history of the migration of the CRM industry to the cloud/SaaS, however, Benioff and team’s execution, coupled with of a product whose nature was conductive to a great business, enabled Salesforce to cross the proverbial Rubicon and see its momentum and flywheel accelerate so much over competitors’ that a similarly capable, or even better team, arriving at a competitor with a good product would not have been able to dislodge Salesforce from its leadership position in its market. This is likely to remain true for as long as no disruptive approach to CRM comes up. And this point is not even just theoretical; mighty Microsoft has been investing and bragging about its Dynamics software suite, which include CRM, for years. Dynamics has taken some market share from others, but without observable harm to Salesforce. Moreover, it is quite conceivable that Salesforce could go on delivering very satisfactory results from its current position for years and years even if the whole management team were to be replaced by poor executives.

From another perspective, it is hard to see where Jeff Lawson and his colleagues could have erred so much to lead to their and the company’s fall from grace. Other than embarking on a crazy spending binge during the years of easy capital in the late 2010s and 2020/21, a blame they shared with Salesforce’s management and which both companies corrected to a large extent in 2022 and 2023, it may be fair to say that Twilio’s management executed quite well, delivering an innovative, best-in-class product and rapidly conquering software developers all over the world to scale revenues quickly. The nature of their business, however, was the prevailing factor in determining the economic outcome of the company. A new management team may squeeze some juice out of such a large company but will not be able to produce the kind of outcome investors were dreaming of in 2021, or even in 2019 by that matter.

“When a management with a reputation for brilliance tackles a business with a reputation for bad economics, it is the reputation of the business that remains intact.” – Warren Buffett

Let’s look at another example:

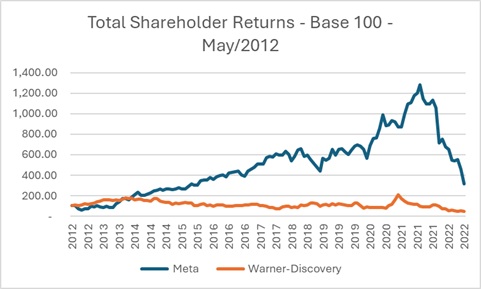

In the chart we see the return of Discovery stock (renamed Warner-Brothers Discovery after the merger on April 8, 2022) versus that of Facebook (renamed Meta) since the latter’s IPO, until October/2022 when it hit a recent bottom (you will understand why soon).

Throughout this period Discovery was managed by David Zaslav, who is, or at least was until a couple of years ago, widely recognized in his industry as a great CEO. He has had a long career in media and managed to produce surprisingly high profits from what most would say were weak brands and cable channels most people could live without at Discovery, before pulling out the merger of his life with Warner in 2022 – he has also been very well compensated by the mogul John Malone. Despite mergers, aggressive cost cuts, and bold strategic maneuvers, Zaslav could not offset the effects of an inexorably deteriorating competitive position and worsening industry structure. Whereas once competitors were traditional media companies very similar to Discovery and Warner, like CNBC and FOX, which did not even compete much because they were all sold together in a bundle that guaranteed recurring revenues, there is now fierce competition from pure-play streamers like Netflix, fiercer direct competition from traditional peers for streaming subscribers, and, importantly, indirect competition for eyeballs from YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, and Tik-Tok. Zaslav’s hand got weaker and weaker from a competitive perspective during this period and that proved to be the prevailing factor for shareholder returns.

Meanwhile, since its IPO, Facebook has continued to consolidate and dominate the social media space, which is naturally prone to a winner-take-most dynamic, and became ever more powerful, recently managing to dodge even Tik-Tok’s innovative, addictive, and deep pocketed attack. Mark Zuckerberg and the leadership team deserve a lot of credit, both for their “move fast and break things” approach to obtain the leadership position early on, and for their ability to make changes to their core products, constantly adapting it to the latest trends. Nonetheless, try to forget the turnaround in Zuckerberg’s image since Meta’s bottom in 2022 – he has amazingly revitalized the company through cost cuts and great developments in AI throughout 2023 and 2024 – and place your mind back to 2022.

At that point, Mark and his company had gone through a handful or more years of excruciating political and societal backlash, Zuckerberg was being mocked for his tens of billions of dollars of investments into the “metaverse” with no return in sight, not to mention wasteful spending overall and a tasteless new corporate name. People saw Zuckerberg as a rogue CEO who could just keep his position due to his super voting rights. Even so, Meta’s shareholders had fared much better than Discovery’s during the period in the chart (since that bottom, Meta’s stock is up more than five times as I write this). Shareholder returns have, first and foremost, reflected Meta’s amazing competitive position, which had been conquered more in the prior decade, as well as its unstoppable profit growth.

In yet another case:

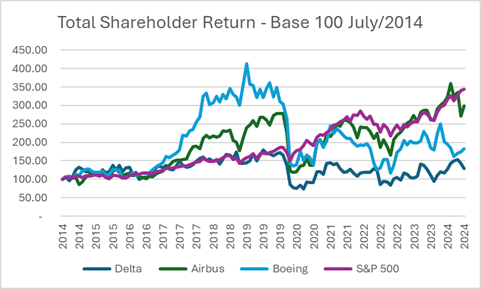

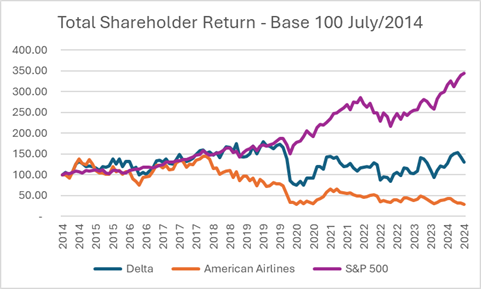

Delta is widely considered the best managed airline in the world. Management has consistently deployed a premiumization and segmentation strategy, predicated on best-in-class service levels and the customer-beloved American Express partnership, all with great capital discipline since coming out of Chapter 11 in 2007 and merging with Northwest in 2008. It also has the best competitive position amid airlines, due to the dominance it has on its main hubs and their geography. When you are from Atlanta or nearby and want a direct flight, for most destinies, your only option is Delta. It has the best returns among its peer group and is enjoying record demand and revenues in 2024.

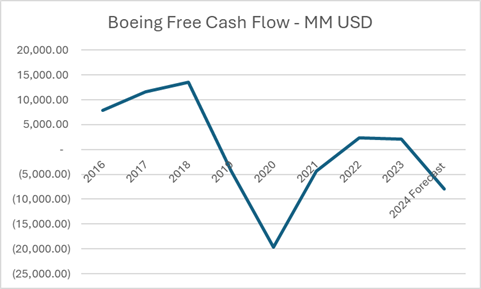

Boeing, meanwhile, may deserve the trophy for the worst managed company of the last decade. It has even pleaded guilty to criminal charges for defrauding its main regulator, the FAA, about the two 737 crashes from 2019, since when it has not been able to produce aircraft with consistent volumes and quality. It has burned through tens of billions of dollars and accumulated roughly $40 billion dollars in debt as of July/2024. The company started to go off rails years ago as management forgot that its main purpose was to develop and manufacture the best airplanes, a mission that requires an engineering-first culture. Instead, they went for a finances-first approach that delivered superb cash flows for a while, but it all came tumbling down in 2019. We could spend a few chapters on Boeing alone.

Airbus has a much better engineering culture, and its products are very well regarded by clients; nonetheless it also has not been able to produce at the volumes and margins that management, clients, and shareholders wish, due to supply chain constraints post-Covid. Airbus’s management must also deal with the subtleties of having the French, German and Spanish governments as effectively controlling shareholders.

And yet, over the last ten years shareholder returns at Boeing and Delta are indistinguishable, while Airbus handily beats both, keeping pace with the superb, mega-tech driven returns of the S&P 500.

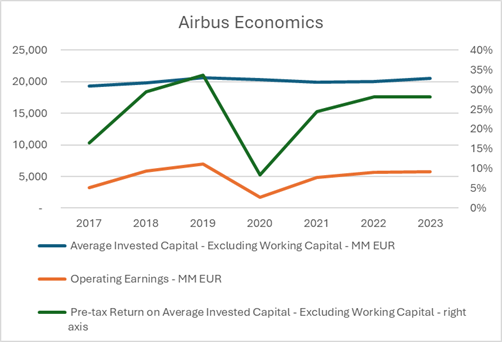

Below we can see Airbus’s main economic metrics. Its working capital position is extremely negative because customers pay so much upfront to get in the line for aircraft delivery that deferred revenues and other operational liabilities are much larger than operating assets, such as inventories and receivables. Invested capital is therefore negative, making the normal return on invested capital calculation useless. In the second chart I exclude working capital from invested capital to give you a sense of how good the business is even without this dynamic. By the way, this great negative working capital position is another evidence of Airbus’s strong bargaining position over the other layers of its value chain, such as airline clients and suppliers.

Moreover, Covid has dramatically impacted the whole aerospace supply chain and curtailed Airbus’s planned ramp up in aircraft deliveries. The company is still much behind its 2019’s plans. Management is working hard to catch up though. If they can get anywhere near their new 2027 targets, operating earnings will roughly double from 2023’s levels, showing the business’s inherent operational leverage and its capacity to retain economic value from growth. Their airline clients, on the other hand, will see their invested capital bases grow even further as they receive and pay for more and more new airplanes, which will pressure their returns down even if the added capacity does not create a new wave of price competition (an optimistic if).

Boeing’s case is amazing.

Despite all the beating the company has taken since 2019, its unsolved problems, terrible financial results, cash bleeding, net debt ballooning to $40 billion dollars, and a vacant CEO position as I write this, it is still a highly valuable business, with an enterprise value higher than $150 billion dollars as of July/2024, and financial prospects that is likely top 95th percentile amid all companies in the aerospace industry. Why? Because, deservedly so, it sits at the top of the industry’s value chain.

The reason Delta can deliver great customer service, safety and a wide range of comfort or affordability options to its customers is that Boeing, throughout its long history, has led the industry in innovation and brought to market remarkable engineering feats. The company has been the pioneer, setting standards in commercial aircraft since the 1930s. Alongside Airbus and engine makers GE, Pratt & Whitney and Rolls-Royce, Boeing has delivered remarkable efficiency gains to the benefit of society – its latest widebody aircraft, the 787, for instance, carries 100 more passengers, flies 50% farther, and is 50% heavier than its predecessor from the 60s, the 707, while consuming at least 50% less fuel per hour. The development of this whole industry sits on these companies’ shoulders. (I am editing this in September 2024 – Boeing has just hired a new CEO, from outside the company.)

Given the incredible complexity of airplanes and the huge benefits to airlines, pilots, and society from standardization (manifested in safety and scalability benefits), the activity of developing and manufacturing commercial aircraft was poised to tremendous consolidation, which happened naturally. Boeing acquired the last significant purely private competitor, Mc Donnel Douglas, in 1997. Airbus has reportedly needed billions and billions of dollars in support, either directly or indirectly, from its government owners to get to its current position – we, travelers from all over the world, should be grateful for this specific government interference given Boeing’s recent woes. I cannot highlight enough how amazing it is to have a unique position, conquered over decades, at the top of large and complex value chains.

If you listen to airlines’ earnings calls, a recurring word is up-gauging. Managers tout the benefits of flying newer aircraft with more seats and greater efficiency to, theoretically, increase revenue per flight while decreasing fuel consumption and diluting fixed costs, such as pilots and land-crew. Ryanair’s famous and outspoken CEO, Michael O’Leary, calls Boeing’s newest narrowbody aircraft “the game changer”, and is constantly complaining he cannot get enough of them. Individually, these decisions to deploy capital on new machines all make sense on paper as savings and incremental revenues from either more passengers or additional premium seats would more than offset the cost of financing the aircraft. As a group though, these decisions create new supply, and when confronted with any demand slowdown airlines recur to the easiest tactic to avoid low occupancy: they lower seat prices. Boeing and Airbus appreciate it all.

After their merger at the end of 2013, U.S. Airways and American Airlines, which had just exited bankruptcy, embarked on an unprecedented fleet renewal plan. Management thought up-gauging was the best way to arrest further market share losses to low-cost airlines, like Spirit and Southwest, which were growing fast with newer fleets. American tried to copy their strategies, cramming more and more people into fuel-efficient airplanes. The value of property and equipment on American’s balance sheet, with a pro-forma adjustment for leased aircraft that in 2013 and 2014 was not capitalized on GAAP financials, expanded significantly as you can see below. Management expected this investment to pay-off through higher earnings, but it backfired as competitors reacted with up-gauging strategies of their own, fare-discounts in some of American’s key hubs, and labor unions demanded better wages from such a seemingly strong company. Operating earnings fell, putting American in a precarious financial position as the most indebted of the big U.S. airlines. Covid further complicated this situation, leaving the company with $33 billion dollars in debt as of December 2023, and the company is now in retrenchment mode, focused on debt pay down - shareholders will likely have to wait until next decade to see any meaningful cash returns.

Delta has fared much better with its high-customer-service/premiumization strategy. It focused on things it could do that low-cost providers could not copy, like exploiting the sheer connectivity of its core hubs and nurturing the Amex partnership, instead of trying to imitate them. Nonetheless, with competitors bringing new aircraft to their fleets and learning to appreciate the value of high-income travelers, even Delta’s disciplined management team could not avoid a huge investment cycle, not only on planes, but also on airport facilities, lounges, etc. Delta is, therefore, being forced to be more like American, while American’s management is striving to be more like Delta as they concentrate all and any growth they can get out of their constrained balance sheet on their core hubs. Delta has been investing more patiently and from a better financial position, however, with higher earnings and lower debt, which stood at $23 Billion at the end of 2023.

This ever-present competition amid airlines that leads them to always want and need the newest airplanes is the beauty of this business, not for them but for Airbus, Boeing, GE, Rolls-Royce, and Pratt & Whitney. These oligopolies drive technological progress. Capitalism takes care of pushing that progress down the value chain, regardless of whether that is beneficial or not for shareholders at the lower layers. Shareholders up the chain appreciate it all.

I consider myself first and foremost a student of businesses. With all the lessons from my life and career so far, my investment rationale is based on studying companies through five questions:

(1) How does the industry’s value-chain pyramid look like?

(2) Where is the company positioned in the pyramid and how does it interact with its peers and players in other layers?

(3) What is the company’s competitive position today and how has it evolved over its whole history?

(4) Does the industry layer in question present favorable conditions and incentives for management to compete rationally and allow companies to create economic value? (Much more on that throughout the book.)

(5) Can I understand enough the whole story to judge with favorable odds whether the company’s competitive position is likely to structurally improve or weaken over the coming decade?

Having burned my mind on those questions, I then eliminate candidates, most of which fall for qualitative reasons. The remaining ones, which are a tiny minority of the universe of companies in the market, will require varying quantitative metrics (valuation and others) to qualify for an initial investment depending on the answers to these same questions, on which the size of the investment will also be based.

Therefore, we, at the fund I run at Tarpon, being micro, long-term investors, have a simpler answer to Howard Marks’s famous “The Most Important Thing” book, in which he has nineteen chapters, each with a different “most important thing”; for us it is all about the competitive position and its prospects. Do not get me wrong though, I agree with Marks on how complex and difficult investing is.