Competition is All that Matters

Part 5

Talking about incentives and human nature, we must always remember that competition is so cruel and entrepreneurs so optimistic that most businessmen, especially the archetypal extrovert c-level executive, downplay the effects of competition. They do that either sincerely because they are naturally focused on their own operations, or somehow misleadingly, usually with good intentions, to rally the troops, raise capital, etc.

When you see phrases like these you can, almost assuredly, understand that the executive is dealing with a tough competitive situation:

“Yes, they are a good company, but the market is big and growing rapidly; we, them, and a few others can all do well concurrently”.

“The market is big enough for all of us.”

“We are an innovative organization, always adopting the latest technologies to be ahead of competitors”.

“We always adopt the latest machinery, and our fleet is always young, which gives us an advantage.”

Explaining worsening results: “We have not seen any material changes in competition.”

“Our relationship with these big platform companies, like AWS, Google and Apple is coopetition… and we can do well, despite their bundles, because customers want the best-of-breed, or because we can do business across platforms.”

“They are a small entrant focusing just on that small piece of the market… We have this big customer base…”

“The next downturn will be different, there is now much more discipline on pricing and discounting amid our peers.”

“We don’t really see them as competitors… we rarely see them in bids. They come to market through that way, and we focus more on this route.”

“We have a differentiated user experience, better content, greater rewards…”

“Private label brands don’t really attract our core customers.”

Asked about an entrant in their territory: “The market is still under-penetrated, and we see it as a positive for the market”.

Justifying declining margins (from already low profit levels): “We are investing from a position of strength.”

Now, the minority of businessmen that go out of their way to say how competitive are their businesses are either utterly frank people or managers of superb monopolies or oligopolies trying to dodge regulators and society’s eyes. Here are some of their typical remarks from people in the latter group:

"We've always had competitors. Our competitors have always been fierce in the technology industry." (Satya Nadella)

"At Facebook, we compete hard because we're up against other smart and innovative companies that are determined to win. We know that our future success is not guaranteed, especially in a global tech industry defined by rapid innovation." (Mark Zuckerberg)

“This market share data is flawed as it defines our addressable market too narrowly.”

“Merchants have many options on how to get paid by consumers.” – mine, but you can imagine which duopoly I have in mind.

And I have an even quicker, perhaps better, tip to spot whether a company is in a precarious competitive position or in a great oligopolistic one. If investors and analysts are the ones bringing the word competition to Q&A sessions with management in earnings calls or industry conferences, it is the former. If management is bringing the word themselves in these conversations or with the media, it is the latter.

A final nice hint of a weak or weakening competitive position can be found in desperate, bet-the-house M&A, either effectuated or known to have been seriously considered.

PayPal is another company whose trajectory was highly altered by Covid. I had long been puzzled by how far the business had come with a rather simple value proposition. If you stop to think about it, the core PayPal button is basically an intermediary between the credit-card ecosystem and merchants, a toll that makes fat profits that account for most of the company’s earnings. Moreover, PayPal’s value added to consumers has been decreasing for years on a relative basis. Since PayPal was invented, Visa, MasterCard, retailers, and merchants acquiring firms have made payments online without an intermediary increasingly easier and safer. Some of the newest and most innovative merchant acquirers, like Stripe, have even ditched PayPal altogether. Meanwhile, the growth of e-commerce software providers with proprietary payment offerings like Shopify and market share gains from giant marketplaces like Amazon have diminished the importance of PayPal to merchants, by disintermediating it.

Nonetheless, by 2019 PayPal still boasted a loyal customer base that kept using it out of habit and the company was growing nicely with the e-commerce tailwind. Merchants kept accepting the button’s high fees at the risk of losing sales in case some of PayPal’s diehard users would abandon their shopping carts. I argue that PayPal’s fees are too high because it charges more than other merchant acquiring companies do to accept credit-cards, while it not only is often funded with bank transfers or debit cards that cost much less, but also does not offer any rewards to consumers. Moreover, PayPal charges the same rate in the U.S. as elsewhere in the world, while in Europe, a big market for its button, credit-card costs are regulated and much lower than in the U.S., making PayPal’s margins there much higher. PayPal may be convenient for existing users, but it is doubtful whether it adds enough value to the e-commerce ecosystem to justify its fees, especially when merchants can match such convenience with cheaper alternatives.

Granted, PayPal was a pioneer in online payments and a major force behind e-commerce growth. Its founders, the famous PayPal Mafia, had grandiose plans for a full-fledged online disruptor to banks. Since the early days, however, the only feature that monetizes well has been online payments. The founders sold the company to eBay in 2002 and left. As it scaled its core product within eBay, the company lost all its innovation power. After the spin-off that brought PayPal back to the public market in 2015, a freshly focused management team not only struck a bunch of partnerships with the likes of Visa, banks, and large retailers, but also accelerated growth efforts to offer commoditized card acceptance services. Their strategy was to keep Gross Payment Volume (GPV) growth at high rates, even if in detriment of take-rate and gross margins – not a bad idea given the hand they were dealt. The core button remained, however, a simple intermediary whose value proposition was under structural decline.

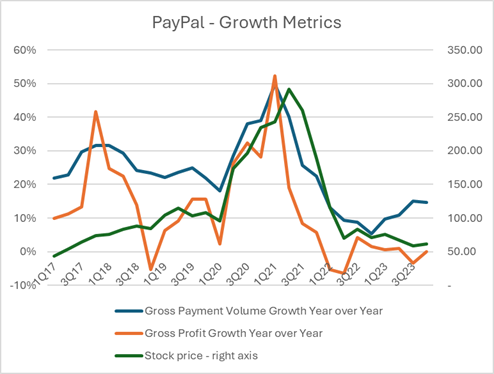

As you can see below, Covid brought an avalanche of payment volumes to the company. Core users deviated a much larger share of their budgets to e-commerce. New-user growth also got a boost as consumers, with their pockets full of savings from government checks and no real-world entertainment options, experimented with buying all sorts of stuff from unknown sources online. PayPal thrived in this scenario during 2020 and early 2021 and delivered rather profitable growth rates that it had not seen for a while. But the hangover came quickly. Competition intensified as the growing online financial services pie attracted venture capital and brought a renewed focus from large tech companies like Apple with Apple Pay and incumbents like banks with their Zelle initiative (a consortium for peer-to-peer and other quick online transfers). Furthermore, Covid accelerated the migration of e-commerce to modern software platforms with proprietary payment offerings, like Shopify. In that turbulent scenario, PayPal’s management, seeing a skyrocketing stock price, felt the need to “find” growth to justify the higher expectations from investors.

PayPal had never successfully managed to create a second profit pool, not even from Venmo, their once hot peer-to-peer money transfer app, but all of sudden shareholders were convinced it would become a full-fledged online bank, making money on deposits, lending (buy-now-pay-later), stock-trading, and physical payments, not to mention crypto-trading. The worst though was what Covid did to the once dormant and discredited Apple wallet. I am not sure what awakened it, probably a combination of factors, such as explosive demand for online payments, renewed management focus, and acceptance by merchants reaching critical mass. But the fact is that it became a very worthy competitor, with huge advantages over PayPal due to its guaranteed distribution on Apple’s devices. By 2020, almost all iPhone users had shared their card data with Apple at least once to make a purchase in the App Store, making a subsequent purchase with Apple Pay highly convenient. I began to see Apple Pay more and more online in places where PayPal’s button was once displayed as soon as late 2020.

By the second quarter of 2021 the deceleration in PayPal’s financial metrics was clear. Management tried to dismiss it as just the post Covid cycle. They renewed efforts to accelerate growth at Braintree, their merchant acquiring arm that competes against Stripe and Adyen in the race-to-the-bottom online card acceptance game, to offset the slump that was happening underneath consolidated figures in the core PayPal button. They could not hide the quicker compression of gross margins, however - you can see in the chart how Gross Profits were decelerating much faster than Gross Payment Volume.

Moreover, none of their new-growth initiatives was working and they provided the market with the clue that the problems regarding the company’s competitive position were quite deep when news surfaced in October 2021 that they were nearing a deal to buy Pinterest, a $45 billion dollar bet-the-house move into a business almost completely unrelated to their own. To understand the magnitude of the bet they considered, PayPal made less than $5 billion in profits in 2021 - Pinterest had never generated any profits in its history. Furthermore, despite early talks from its management team that Pinterest had potential to expand from its niche social media position into facilitating commerce for its members, there was no real substance to support a thesis of relevant synergies. To the opposite, one could argue that by trying to help Pinterest become more of a marketplace PayPal would compete with and alienate other marketplaces that bring significant volume to it, like Etsy and eBay.

Many shareholders took the clue and began to sell PayPal stock immediately, accelerating the downward spiral and likely pushing management to give up on Pinterest. From there it has been a long downhill, with management changes, activist investors, and an ongoing struggle to avert market share losses. By the end of 2023 PayPal was worth just a little over $60 billion – it almost paid $45 billion to buy Pinterest, let that sink in.

Another botched Hail-Mary acquisition attempt happened at the same time. In October 2021, Zendesk tried to buy Momentive, which had renamed itself but was still the good old SurveyMonkey that had long been disappointing its shareholders, in an all-stock deal that valued Momentive at more than $4 billion. Zendesk is a provider of cloud software for customer service. We can call it a second-generation product in the field, coming after large incumbents like Salesforce with a modern product that gained traction with startups, especially in the venture-backed world of the 2010s where startup founders with pockets full of cash were buying the latest software products without much consideration for cost.

Zendesk certainly had a nice product and scaled quickly. By the late 2010s, however, growth had slowed as it could not broaden its customer base much further. In the enterprise market it bumped against giants like Salesforce that sell customer service software bundled with CRM and other services, while in the long tail market of SMBs dozens of competitors from all over the world were offering cheaper solutions. Real profits, after share-based compensation, were elusive.

As everything digital, Zendesk got a bump up from Covid, but by mid-2021 reality was striking back and the management team, still led by the founder, announced the high-priced Momentive deal, vowing growth synergies that no one from the outside could understand. Furthermore, SurveyMonkey, a low growth business, was under attack itself. Free or freemium survey software options from Google and other startups were taking share amidst SMB customers, while, in the upper end of the market, more sophisticated and modern solutions like Qualtrix were rapidly gaining ground. Shareholders took the clue, and Zendesk’s stock began to fall. Activist investors jumped in and pressured management to terminate the deal.

No one in Zendesk’s management team, including the founder, had significant ownership in the business. They were likely first and foremost motivated to defend their positions as high-profile executives in the Silicon Valley tech community. This became even more exposed when they turned down an acquisition offer for Zendesk itself early in 2022, for $17 billion, while they were still fighting their own shareholders to complete the Momentive deal. The disputes and intrigues got uglier from there. In the end, Zendesk did not buy Momentive and management agreed to sell the company to a consortium of private equity firms for $10 billion in June 2022. The new owners would likely come up with a completely new strategy, lower growth expectations, and cut costs dramatically. I remember initially being puzzled by the seemingly low valuation of the deal but understood it when I read all the regulatory documents around the sale (public traded companies must disclose how these transactions unfolded behind the curtains).

Zendesk was under much more severe trouble than I had imagined, with new customer growth grounding almost to a halt. Potential buyer after potential buyer had looked at their internal data and passed on bidding. Software is a great business model and Zendesk’s customer base seemed sticky. But when a software company’s valuation and business plan (to reach profitability) depend on continued growth in net-new customers for years to come, investing in software can become quite dangerous, unless there are strong forces, such as network effects, niche market dynamics, or standardization trends, supporting a thesis that the company in question in highly likely to remain the chosen option for new customers. Zendesk’s existing revenue base was somehow protected, but its broader addressable market was not. Entrants, from small players all over the world to highly financed ones, like Intercom, ended up inflicting severe pain.

Management had given investors a great tip on the business’s deteriorating competitive position almost a year before the disappointing sale, when they announced the Momentive deal – wise were those who took it and got out of the sinking ship. Even wiser were those who never really considered investing in Zendesk, recognizing it had never managed to reach a stable dominant competitive position. To close on this sad saga, Momentive would be taken over by private equity too, for $1.5 billion in 2023.

The point may be made, but I cannot finish without an example of a closed deal, actually two – this company was really desperate. AT&T is currently known by most as one of the three national wireless carriers in the U.S. It also offers wireline telecom services in almost half of the country, through assets inherited from the old Ma-Bell system, built in the late 1800s and early 1900s. These lines were all originally built with single copper threads well suited to carry telephone signals. They can also be used to carry internet signal but are extremely ill suited for that when compared to either fiber optics or the multi-thread copper cable technology that cable-TV companies had already rolled through most of the country by the 90s when broadband started to take over from telephone as the main product households and businesses would buy from telecom companies.

Summarizing, the writing was on the wall; AT&T’s management has known for decades that their revenues and profits from customers connected by single copper lines would all wither away over time as customers migrated to cable or fiber competitors. Moreover, fiber is a better technology for broadband than cable and AT&T had a great jumping point to deploy it on its network by replacing copper with fiber. That would be much cheaper than building a whole new fiber network from scratch, the only alternative for would–be entrants. Management was well aware of that and even started a program to roll out fiber in Austin as early as 2013 and saw that it worked.

Nonetheless, rather than face reality and communicate to shareholders the need for much higher levels of capital expenditures (a term that telecom investors dread) to upgrade to fiber fast and at scale all over the country, a plan that would likely entail dividend cuts, management spent years going very slowly with fiber, often postponing already announced plans to enter new cities. Instead, AT&T’s leaders, aware of their quickly weakening competitive position in wireline, as well as in wireless due to T-Mobile’s disruptive growth strategy during that period (a story we will come back to later in the book), did not one, but two large desperate acquisitions to try to escape their predicament in a fun rather than painful way.

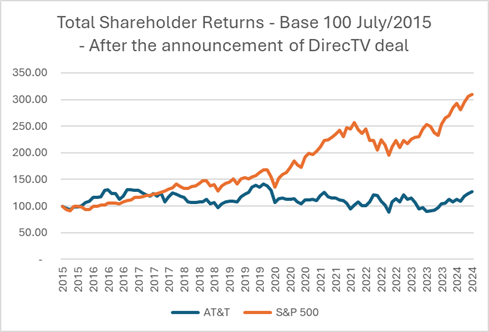

First, in July 2015, they acquired DirecTV, a satellite provider of TV-bundles, for $49 billion, at a time when the pay-TV ecosystem was already losing subscribers due to the growth of streaming services. It gets worse, DirecTV satellites were worthless for broadband connectivity and, therefore, useless to fight back against cable or fiber companies in the broadband era. AT&T ended up de-consolidating DirecTV into a JV with private equity firm TPG in 2021, at which point subscribers had fallen by almost 2/3 since the time of the acquisition. AT&T will never even come close to recouping the principal it spent to buy DirecTV.

Second, in 2016, AT&T announced the bold plan to buy Time-Warner, the media content giant, another company that was under pressure from streaming, as well as from indirect competitors like social media. After going to courts to fight regulators who wanted to block it, AT&T completed the deal in 2018, promising huge synergies. Media, however, is a completely different business, diametrically opposed to telecom on the kind of personalities and skills needed from executives. Including debt, AT&T paid $109 billion for Time-Warner. Things went so bad under AT&T’s ownership that just three years later management announced a deal with Discovery to spin-off Time-Warner, eventually getting back $40 billion dollars in cash and another $40 billion dollars in Discovery shares that they distributed to their shareholders (those are now worth a third of that).

During this period, AT&T was led by Randall Stephenson. I am not sure of this, but reportedly the strategist and negotiator behind both acquisitions was John Stankey, who became CEO in 2020 and took the bitter pill to reverse both deals and refocus the company on basic telecom services. Moreover, he cut the dividend and went all in on fiber and 5G, increasing capital expenditures significantly. It is a complete 180-degrees shift in strategy that seems to be working – at least it has stabilized the company. If it is true that Stankey championed the acquisitions and managed to change his mind so drastically, this man deserves all my respect. Shareholders, however, would have done much better by staying away from him and the company all over this period, recognizing the clue about the core business’s deteriorating competitive position that management clearly gave with their two desperate acquisitions in the mid-2010s.

Before we move on, capitalism is terrifying for shareholders. But terrifying does not mean bad. Individual shareholders must deal with uncertainty and risks but can manage for great outcomes. Most importantly, capitalism is the best economic system, for both society and shareholders as a group, which in a truly functioning capitalist system should encompass the entire population. Everyone should save for retirement and dedicate part of those savings to finance businesses, direct or indirectly, to try to boost returns. There is virtually no chance for honorable individuals to be shareholders in socialism or communism where just political leaders with bad characters can open those doors without being defrauded.

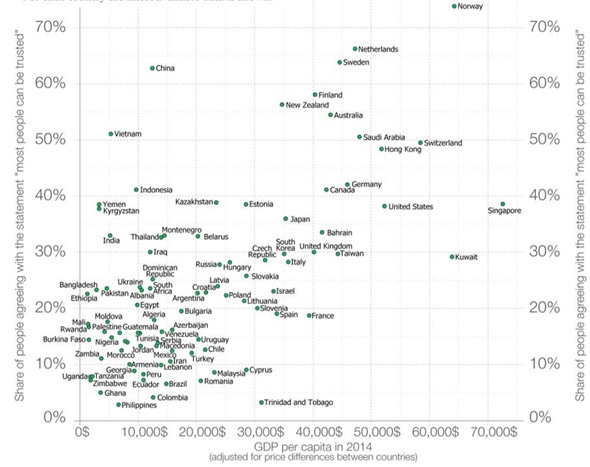

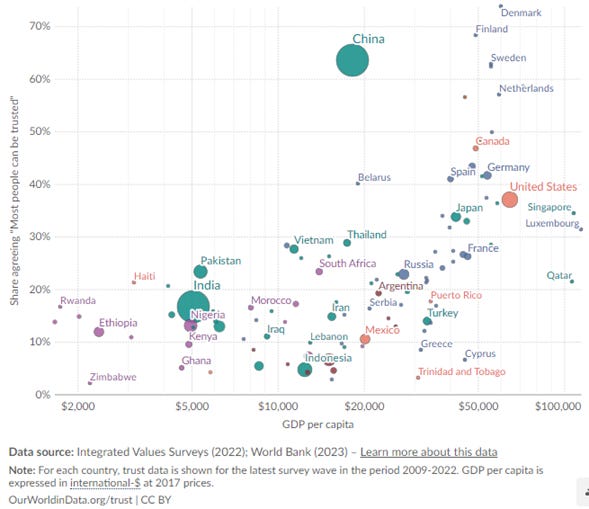

Moreover, cronyism, which is a capitalist system dominated by corruption, is the ultimate example of the proverbial guy in a crowded stadium standing on his feet to better see the field just to provoke a chain reaction that leaves everyone standing up, in a less comfortable position, with no better view. Businesspeople are often tempted to cheat, exploit someone else’s trust, or even do illegal things such as engaging in price fixing agreements with competitors. We must all resist those temptations and, like Buffett, continuously preach and praise honesty. Trust is the most crucial factor determining the economic success of a society. Even the smallest cheating is akin to standing up on your toes to eventually destroy trust and wealth.

Source: Coyle, Diane - Trust and Productivity Growth - An Empirical Analysis

My intention with this book, therefore, is not to argue for the formation of oligopolies all over the economy, in all layers of value chains just so that shareholders can do better - that would be anathema with my love for capitalism and lead to an outcome like what communism or cronyism creates. To the opposite, my intention is to simply and pragmatically recognize the fact that the nature of capitalism, competition, psychology, and technology will push shareholder returns down to meager levels at most companies, while creating a few oases of wealth. I am all for appreciating, understanding, and living with that reality.

1- Other Levels and Indirect Competition

At a first impulse, one might say that analyzing competition is simple: list all players and their market shares over time then break down their financial statements. Consolidated industries will show better returns on invested capital and slow-moving market share positions point to favorable conditions for shareholders.

The classical “easy” example is Coke and Pepsi in the U.S. market, where an equilibrium of sorts was found decades ago, to the great benefit of owners. The soda market has settled down. These two giants make the bulk of profits, sitting on top of their value chain, managing marketing and coordinating franchised bottlers and distributors. Nonetheless, even when analyzing and pondering the future of this simple industry, we must think at other levels. For instance, will indirect competition from healthier drinks ultimately hurt volumes to such an extent that the duopoly will lose profits (or at least see their economic relevance slide as a percentage of GDP), as has been happening with once superb beer brands? Will at some point society push back against unhealthy foods to a much greater extent than we see nowadays, bringing consumption down? Or even try to regulate or penalize these companies as happened with tobacco firms?

Until about ten years ago, beer companies were widely regarded as some of the best businesses in the world, with great returns and attractive prospects for profit growth due to their oligopolistic pricing power. Brazil’s Jorge Paulo Lemann and his two partners became multi-billionaires and famous all over the world mostly based on their success in the sector starting with a local brewer, Brahma. They consolidated the Brazilian market through wise M&A, executed their cost cutting playbook based on a strong meritocratic culture, steadily raised prices, and achieved profit levels that enabled them to go global and eventually own many of the best brands in Europe, as well as the storied Budweiser, through their giant company, Anheuser-Busch InBev (BUD).

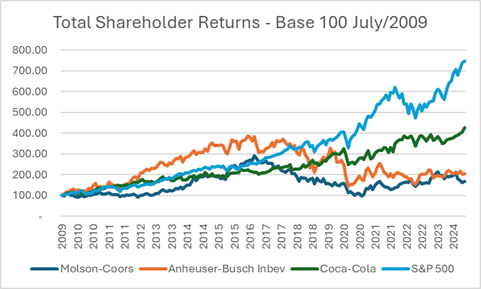

Beer was such a great business that they did not have to innovate much or change the business model. Long standing dominance with distribution channels and consumers’ habits protected the business from competition. “All” that they had to excel in was managerial execution, which they did, significantly “beating” peers in that regard. In most countries less than a handful of players dominate the market and exercise pricing power, competing through marketing and brand positioning – a rather healthy form of competition. It all seemed perfect and unassailable. Molson-Coors, with greater business concentration in North America, was also flying high and is a cleaner case study. The chart below indicates that something relevant happened over the last eight years, however.

The main attack did not come from within the industry – that happened too, with Mexican brands gaining ground, but was not the main problem. Even Constellation Brands, the owner of the top performing Mexican brand Modelo in the U.S. market has seen its share price underperform the S&P 500 significantly over the last eight years. Beer companies have lost economic relevance both because consumers have gravitated towards other forms of alcohol consumption, especially less caloric ones, and because there is a growing trend, particularly among younger generations, of lower alcohol intake, which is quite concerning for the beer giants as it will create a long-lasting downward pressure on volumes.

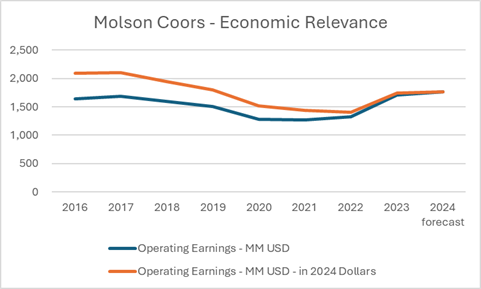

Indirect competition can be as damaging as a rogue peer. We can see below how much of a struggle it has become for Molson-Coors to deliver any growth at all. Beer volumes have fallen 22% between 2015 and 2024. Revenue has just grown slightly due to pricing/inflation. Nominal earnings are up 8% since 2016 (cumulatively), but down 15% when adjusted for inflation. In other words, the business has lost economic value in real terms. It lost even more relevance compared to the broader economy as real GDP has expanded by 20% during this period.

Coincidentally, a week or so after I wrote these paragraphs above, I listened to an episode of How I Built This, the podcast from Guy Raz with entrepreneurs. He interviewed Michael Houlihan and Bonnie Harvey, founders of Barefoot, the company that pioneered the strategy of making wine more approachable to American households in the mid-80s. They recount how the wine industry was focused on exquisite, inconsistent, and high-price products, while they saw consumers that wanted the opposite, a more beer-like wine. They even stole marketing tactics from the beer industry. Like any good entrepreneurial story, it was a struggle in the beginning; wine veterans at the time despised their strategy. Michael and Bonnie sold Barefoot to wine giant EJ & Gallo in 2005 – their creation has since grown to be the largest wine brand in the world. It took time, but Barefoot and copycats came to bother the beer giants. It was an attack from the corners, which the eyes of beer executives did not catch or pay attention to for years.

Take banks, until the deregulation wave in the 80s, competition was fairly limited, and life was easy for bankers who could deliver satisfactory returns to their shareholders without incurring significant risks or having to innovate. Joseph Nocera published a great book in 1994, called “A Piece of the Action”, in which he described the wave of newcomers that had attacked and reshaped the banking industry. So much had changed over the prior decade that defining banking as an industry had become useless for a good analysis of competition – the scope had to be significantly broadened to include mono-line card issuers, brokerage houses, non-bank mortgage originators, etc, in what we now deem the financial services industry.

Richard Fairbank, Capital One’s CEO to this day, alongside Nigel Morris, had the idea of using data analysis to segment and target customers with specific credit card offers all over the country by direct mail in 1987. They launched their new venture inside Signet Bank (later acquired by Wells-Fargo) in 1988 and grew so quickly that by 1994 Signet had spun-off the new business so that shareholders could enjoy its high-growth prospects directly. Once upon a time banks competed almost exclusively amidst themselves in consumer lending. By the time Capital One was gaining scale that was far from the case already, and the space would just get more and more crowded.

Today, Capital One is a bank itself, having acquired depository institutions over the years and built a large balance sheet. But indirect competition in consumer lending keeps evolving and proliferating. Newcomers like Affirm, Klarna, and others not only take market share and fight on pricing and promotions, but also often wreak havoc in credit-score data disturbing underwriting models. No good competitive analysis of retail banks can disregard these non-bank payment/lending players, not to mention non-bank lenders in other fronts, such as subprime auto, as well as alternative offerings and companies focused on the asset side of consumer’s balance sheets, such as money market funds and online brokers like Charles-Schwab that compete against banks’ deposit and wealth management services. The same is true in corporate and investment banking, where private equity firms that used to be just profitable clients for the likes of JP Morgan are now unashamedly stealing banks’ lunches.

We have also already seen how traditional TV companies lost a lot of ground to streaming. But that is just part of the story. They have likely lost much more to social media and other forms of entertainment. Netflix’s founder, Reed Hastings, once said that his biggest competitor might well be Fortnite, a multi-player interactive game loved by teenagers. We can go further; digital entertainment competes with “real-world” options, such as a trip to Disney, for consumers’ minds and pockets. That trip, in turn, might compete against a new couch or smartphone.

In the B2B world, that brand new office building project might compete for resources against a new ERP system. It is not a zero-sum game, but at some point, all industries compete for societal resources against each other. Such movements of attention, demand and capital flows among industries tend to be gradual, but they can compound into a powerful force disturbing or boosting a given sector over time; hence, they cannot be overlooked. On the other hand, we must remember that many of these trends revert to normal.

During Covid, many bold prognosticators claimed the death of corporate travel and some leisure options like crowded cruises, only to be proven wrong. It is the job of a good long-term investor to read widely and ponder these broad trends carefully. So long as we have a wide enough view for the set of competitive products/services we are considering in our core analysis, these broader societal trends are rarely amid the top three factors that will define the success of an investment, although they are usually the most chatted about as they make up for great water-cooler conversations. A company’s position in its value-chain, structural competitive forces in its industry, the level of market concentration, and the maturity stage of its industry are normally more relevant – but there are important exceptions, such as we saw with the beer giants.

But to be clear, “indirect” competition is often among the top three factors requiring close attention. For instance, when analyzing a cable-TV company, like Warner, one cannot overlook Netflix, YouTube, Instagram, and Tik-Tok. A good investor needs to learn where to draw the line separating “indirect” competitors that are impactful enough to be treated as seriously as, or even more respectfully than, direct competitors, from broader, often fleeting societal changes with minimal effective impact.